Luigi Nono // Franz Liszt

Canti di vita e d’amore. Sul ponte di Hiroshima / Eine Faust-Symphonie

octoberoct 3

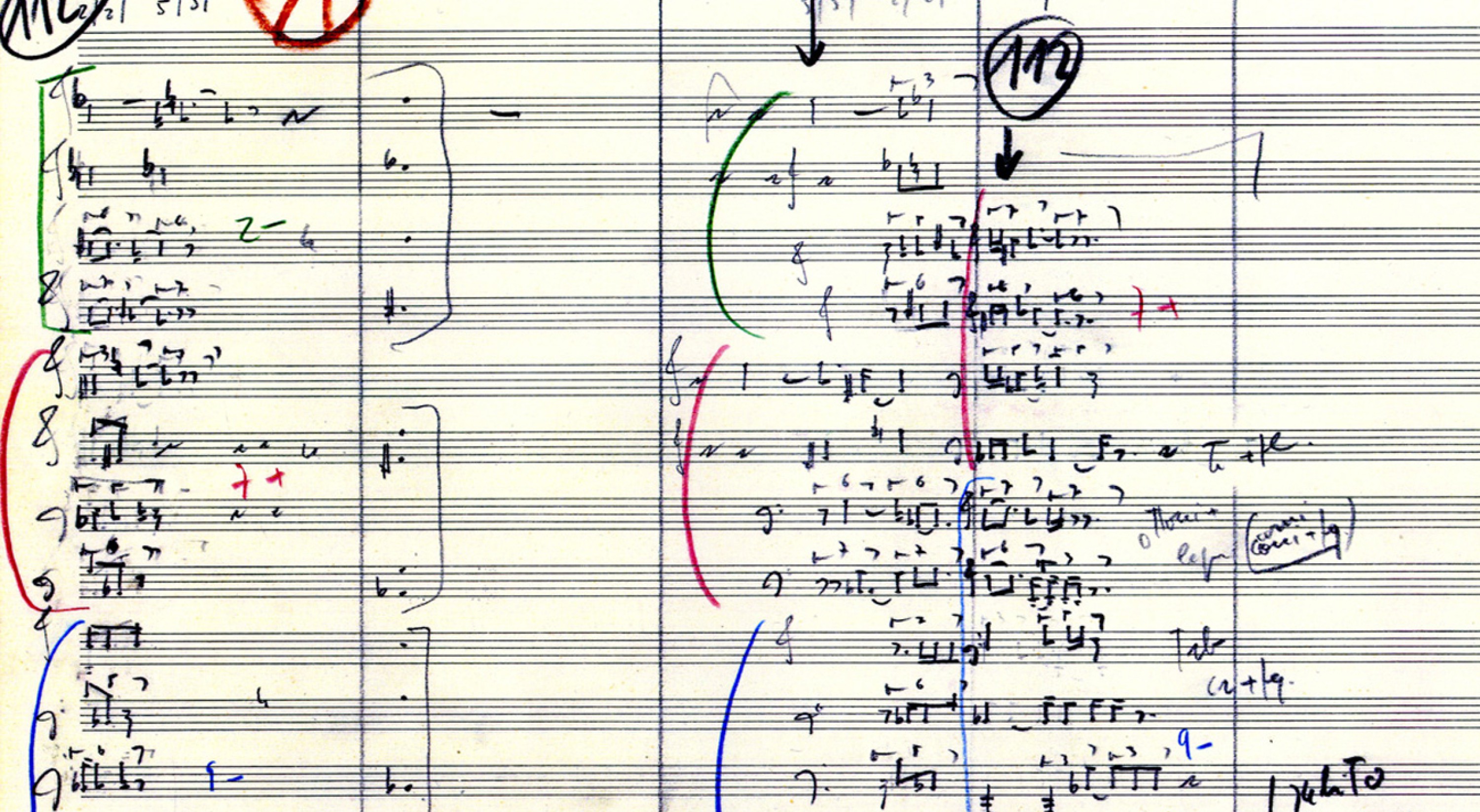

Luigi Nono, Canti di vita e d’amore. Sul ponte di Hiroshima

Franz Liszt, Eine Faust-Symphonie

Anu Komsi, soprano

Andrew Staples, tenor

Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France

Men’s Choir, Radio France

Sébastien Boin, choirmaster

Tito Ceccherini replace Mikko Franck, conductor

Coproduction Radio France and Festival d’Automne à Paris

With the support of Mécénat Musical Société Générale and the Ernst von Siemens Foundation for Music

Same concert/program: Festival de Laon (Cathedral), Laon, October 1, 8.30 PM (bookings: 03 23 20 87 50)

The concert in Paris will be recorded by France Musique radio station.

Canti di vita e d’amore (Songs of Life and Love) by Luigi Nono cover three subjects: mass destruction, the tortured individual, and hope, both uncertain and impatient.

Dramatic blocks of orchestral sound conjure up the 200 000 victims of the bomb that hit Hiroshima and which is cursed for eternity in the song of a man whose face and hands are burnt by radiation. A veil conceals his face and, instead of fingers, a steel claw plucks the delicate strings of the instrument. Nono developed ideas of the philosopher Günther Anders (1902-1992), author of The Atomic Threat – Radical Considerations, seeing nuclear death as a warning, and decrying our blindness in the face of the apocalypse.

The second movement is a monody, intense and pure, where the solo soprano provides the voice for Djamila Boupachà, a prominent figure in the Algerian independence movement, a symbol of life, love and freedom in her constant struggle against colonial oppression and the torture she suffered at the hands of French troops.

The last movement includes verse by Cesare Pavese (1908-1950) in a song of joyfulness, striking strings, and with bells and metal resounding vibrantly, extolling love, not beyond the realms of reality, but “in the awareness of life.”

Nono, as a musician of political Utopia, challenged any idea of naive humanism as being, by definition, powerless. In contrast, Franz Liszt, in A Faust Symphony, offers a spiritual interpretation of redemption with a celestial image of peace and serenity. There is his supreme mastery of long developments built on simple motifs or even simple intervals, and also the orchestral virtuosity of the three portraits of characters from Goethe: Faust, Gretchen and Mephistopheles, the third being the figure of negation, solely employed in distorting and destroying the previous themes. But in the atomic age, as Günther Anders suggested, perhaps the Faust who dreamed of being a Titan has already died.